Agroforestry and biodiversity: overlooked drivers of agricultural production

14th October 2022

At an online event hosted by Trinity Global Farm Pioneers, expert speakers discussed how agroforestry and biodiversity can help drive agricultural production and explored the barriers to uptake among farmers. Henrietta Szathmary writes.

The webinar was free to attend and took place on 11th October as part of Countryside COP 2022. At the end of the event, attendants had the opportunity to share their thoughts and ask questions through a dedicated Q&A session.

The webinar was opened by Emily Pope from Global Farm Pioneers, who introduced the speakers and said a few words about the event’s host.

Global Farm Pioneers is a free-to-use virtual knowledge exchange platform that provides spaces for sharing ideas and advancing best practice. Through the platform, users can connect with like-minded people, attend and host online events, and expand their knowledge in areas of interest relating to agriculture.

The benefits and limitations of agroforestry

The webinar’s first speaker was Martin Lukac, professor of ecosystem science at the University of Reading. In his talk, he gave a broad overview of the benefits and limitations of agroforestry and shared details of a study looking at farmers’ attitudes to adopting farm woodland.

To begin with, Prof Lukac introduced the concept of agroforestry, which he defined as “the purposeful integration of woodland with an agricultural production system”. Its two main types, he explained, are silvoarable (trees + crops) and silvopasture (trees + grazing livestock) systems.

He then gave a rundown of the various benefits agroforestry can bring to traditional farming and the wider environment. He emphasised that the greatest benefit comes in the form of ecosystem services, such as increased pollination, natural pest control, and carbon sequestration.

According to Prof Lukac, the benefits of agroforestry relate to:

- Diversification

- Biodiversity

- Carbon

- Soil protection

- Pest regulation

- Climate regulation

- Resilience

- Stability

- Landscape amenity

As for its limitations, the three main factors outlined by the professor were establishment cost, management complications, and opportunity cost. Elaborating on the latter, he explained that trees can decrease crop productivity by overshadowing the plants and competing for nutrients, which represents a concern for farmers.

Prof Lukac also shared details of a recent study that surveyed 2,000 farmers in the South East and East of England about their views on adopting an agroforestry system.

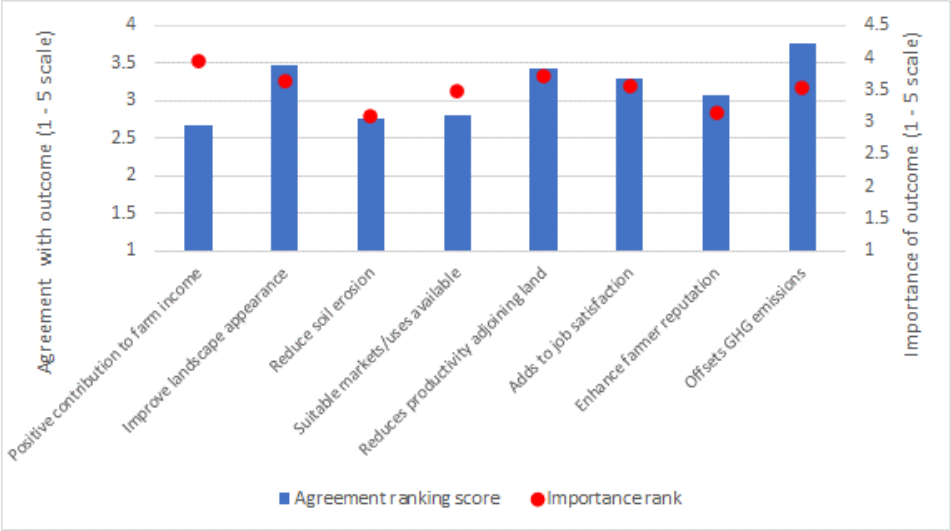

The results showed farmers considered a positive contribution to farm income to be the most important factor when it came establishing woodland on fields, followed by the reduction in productivity of adjoining land and improvement to landscape amenity.

The results have also shown that farmers widely believe implementing agroforestry would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve landscape appearance. On the flipside, many also believe the system would reduce yields on nearby land due to competition between the trees and the crops.

These findings are summarised on the figure below:

Survey results showing farmers’ attitudes to adopting farm woodland or agroforestry in South East and East England. (Felton et al., 2021)

Overall, Prof Lukac believes the small and large-scale benefits of agroforestry outweigh the costs in terms of landscape productivity and ecosystem services. However, he warned that many farmers don’t know how to get started with agroforestry, and providing the necessary support will be critical to uptake.

Agroforestry increases pollination for arable crops

The next speaker of the event was Dr Alexa Varah, postdoctoral researcher at the National History Museum, who covered how agroforestry systems affect environmental outcomes like biodiversity and pollination.

In her talk, Dr Varah presented an applied research project she carried out with colleagues to determine the environmental benefits of agroforestry systems. The project compared four silvopasture and two silvoarable sites with monoculture controls using six UK farms.

Although the study measured a range of environmental outcomes, Dr Varah highlighted biodiversity and pollination in her talk.

To measure the abundance and diversity of pollinators, the number of bees, butterflies, and other insects were recorded on all sites using pan traps, Dr Varah explained. Pollination was also directly measured by counting the number of seeds produced by potted plants on the fields.

The findings have revealed that agroforestry systems attract a higher number of pollinators and insect species than monoculture systems. Fields with woodland had twice as many bumblebees, solitary bees and hoverflies, with some sites giving home to over 10 times the number of solitary bee species compared to control fields.

Moreover, plant pots produced more seed in agroforestry systems, indicating higher pollination. This underlines how increased pollinator presence can directly benefit crop yield in silvoarable systems.

Dr Varah also pointed out that the choice of tree species will have an impact on how insects and other wildlife respond. In a silvoarable setup, she suggested taking advantage of the understory and establishing flowers or vegetation to support pollinators or biodiversity.

In her conclusions, Dr Varah echoed Prof Lukac highlighting that agroforestry systems are a more efficient way of using land due to more biomass being produced, which in turn increases the landscape’s carbon storage capacities.

Integrating biodiversity to support agriculture

The final speaker, Dr Ben Woodcock, gave his talk on the sustainable intensification of farming systems to support biodiversity and crop yields. Dr Woodcock is an ecologist at the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

First up, he discussed how intensive agriculture is likely a major contributing factor to the rapid decline of pollinator species in the last few decades. While bringing biodiversity back into agriculture is key to retaining important insect species, farmers will show reluctance unless they see a benefit to yield, Dr Woodcock said.

To expand the existing evidence base that biodiversity can support agriculture, Dr Woodcock and his colleagues conducted an experiment implementing the approach at landscape scale.

The study was carried out at the 1,000-acre Hillsden farm which previously used an intensive farming system and was heavily reliant on agrochemical input. The farm was split into 15 farmlets of 50-60ha each, where three different treatments were applied:

- Treatment 1: Business as usual

- Treatment 2: 3% land removed to wildlife habitats

- Treatment 3: 8% land removed to wildlife habitats

Wildlife habitats could include field margins or field corners and were created to promote biodiversity not yield; Dr Woodcock stressed. Yield maps were then used to monitor changes to crop production over an extended period of time.

After five years of running the study, the results were analysed and related to the regional average. While yield from control crops remained just below average, there was a gradual increase in yield from crops that received the second and third treatments.

The findings are displayed in the graph below:

Changes in crop yield under different treatment conditions. The dashed line represents the regional average (Pywell et al, 2015)

As seen on the graph, there is a time lag before crops grown in systems integrating biodiversity start producing higher yields. Dr Woodcock said the lack of instant turnaround that can be easily achieved with agrochemicals is the main reason why farmers are reluctant to implement such systems.

To find out whether the results of the study are generalisable, Dr Woodcock and his colleagues conducted another experiment across 18 farms that use various farming systems. Treatments similar to the previous study were applied over a period of four years, and preliminary results show crop yield responded best to more complex biodiversity treatments.

In summary, Dr Woodcock pointed at the growing scientific evidence that biodiversity can support agricultural production, but said it will never become the sole solution to increasing yield.