Trace elements for lambs

1st June 2022

Lambs can be prone to a great number of health and productivity problems while on pasture and many succumb to borderline trace element and vitamin deficiencies. Veterinary pharmacologist and advisor to Provita Ltd, Dr T.B Barragry, offers a guide to the most common deficiencies and the benefits of drenches.

Adequacy of nutrient intake by young lambs can be hit and miss in many cases, depending on weather conditions, soil type, parasitism, pasture quality and herbage type.

It is therefore not surprising that many lambs on pasture succumb to borderline trace element and vitamin deficiencies, which may or may not be obvious to the farmer. Outward clinical signs may be minimal but the result is seen in the extra time taken to gain bodyweight and susceptibility to other diseases. Clinical signs are frequently mild, nonspecific and insidious in onset, such as poor growth rates, weak lambs, ill thrift, or reduced feed intake. Problems tend to affect the whole group rather than individual animals.

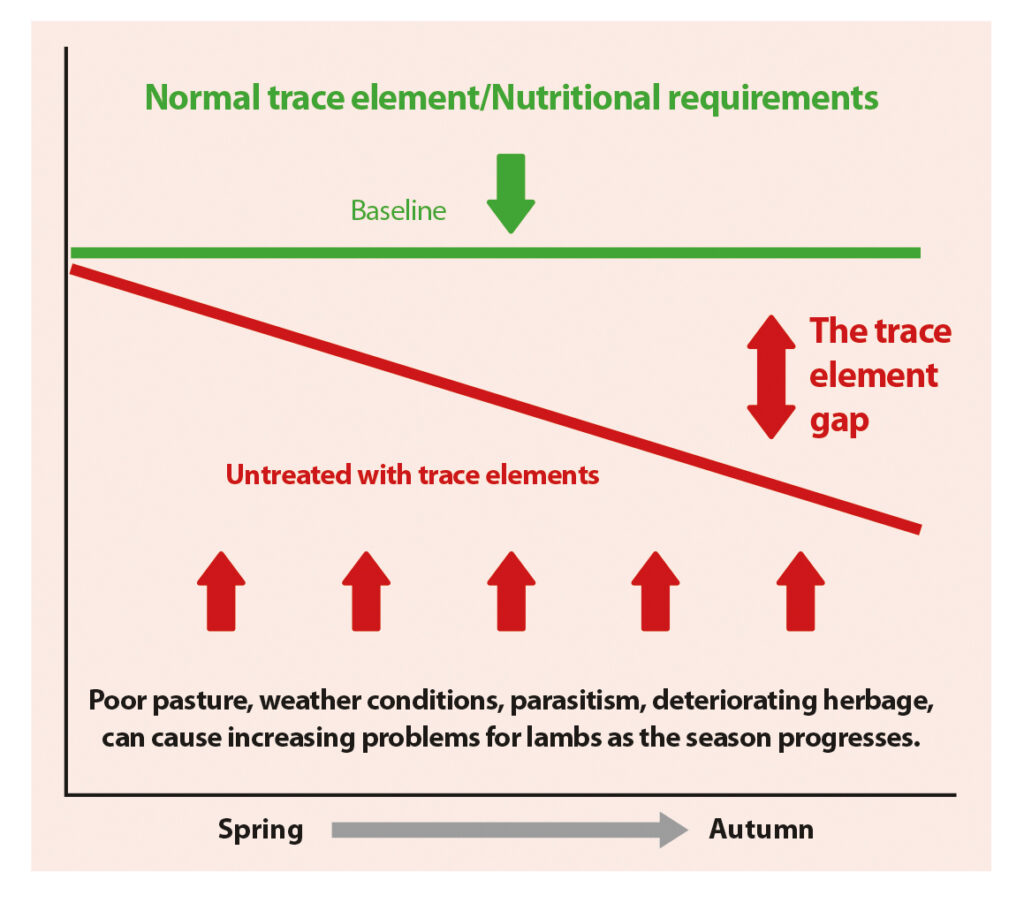

Maintaining a stable trace element status can be a challenge in many sheep flocks. During the season, many sheep are exposed to poor quality grazing and forage which possesses quite low trace element and nutritional values. Lambs are also subjected to the stresses of harsh outdoor conditions and extreme weather variations on hillsides.

Occasional foot problems in lambs can significantly impede mobility and grazing and lead to inadequate nutritional intake. Soil and herbage composition can vary in different geographical areas and can determine the various specific trace element deficiencies that are found in local regions. As the season progresses, the decreasing quality and availability of herbage increases the risk of problems occurring.

All these factors acting together can contribute to borderline deficiencies of selenium, vitamin E, vitamin B12, copper, cobalt, zinc, and iodine in sheep. Trace element shortages all negatively impact the general health of the lamb and also lower its immunity status, which can predispose it to parasitic infestation.

Copper: Copper deficiency can occur when sheep graze pastures low in copper but more often it occurs in pastures high in iron, molybdenum, and sulphur. Where two or more of these elements exist together on a farm in quite ‘normal’ concentrations, they will act to bind out copper from a diet.

Swayback is the most common sign of deficiency and is a progressive hind limb weakness that leads to paralysis, caused by damage to the spinal cord during foetal development mid-pregnancy in copper-deficient ewes. Copper deficiency in older animals has been linked to poor fleece quality, reduced growth rates, anaemia, and increased susceptibility to bacterial infections. Copper supplementation will be necessary in these animals bearing in mind that sheep are susceptible to copper poisoning.

Cobalt: Cobalt is an essential precursor of vitamin B12 and is synthesised by the rumen micro-organisms. The symptoms commonly associated with cobalt deficiency manifest themselves as a result of a lack of vitamin B12 in the animal, rather than of cobalt. Clinical signs of cobalt deficiency are usually observed in weaned lambs at pasture during summer and autumn. Signs include lethargy, reduced appetite, poor quality wool with an open fleece, small size and poor body condition despite adequate nutrition.

Cobalt deficiency (‘pine’) in autumn results in ill-thrift, lethargy, poor appetite, watery ocular discharge, and poor fleece quality. As a consequence, lambs have poor immune function and are often more prone to infectious disease (e.g., clostridia, Pasteurella). Parasitic disease will exacerbate clinical signs by reducing gut vitamin B12 absorption, sometimes resulting in symptoms of deficiency even when nutrition and dietary cobalt levels appear to be adequate.

Selenium/vitamin E: Selenium deficiency occurs in soils of certain geographic areas and can lead to pasture/crop deficiency. A primary clinical sign of selenium deficiency is ‘white muscle disease’, although disease prevalence is low. Usually, rapidly growing lambs are affected, with sudden onset generalised stiffness, which may progress to an inability to stand within a few days if left untreated. In older growing animals, selenium deficiency has been linked to poor daily liveweight gain and in breeding ewes can cause embryonic death and poor fertility performance.

Iodine and manganese: Iodine is central to a good feed conversion ratio and weight gain. The utilisation of iodine in the body also depends on selenium, which is a co-factor in the synthesis of thyroid hormone. Deficiency is typically associated with an enlarged thyroid (goitre), stunting of growth and results in late abortions, stillbirth and/or increased lamb mortality. Some soils may be iodine deficient (primary deficiency) whereas brassica species such as root crops, rape and kale contain goitrogens which block the uptake of iodine (secondary deficiency).

Manganese deficiency is rare; however, symptoms such as joint or bone abnormalities and a stiff gait are reported, along with potential negative effects on fertility due to poor oestrus expression and conception rates.

Trace element and vitamin drenches

Oral drenching is usually less expensive than boluses and allows for targeted delivery to certain animals, or at specific stress periods during the grazing season or winter housing, where only short-term cover is needed. It may also be more cost effective in the long term insofar as it targets delivery to the most susceptible animals.

Other advantages:

- A larger number of trace elements can be included

- Vitamins can be incorporated into the formulation also (vitamins E, A, C, D, B) which

can act to potentiate some of the actions of the trace elements and thus boost overall effectiveness in the short term - High concentrations to address the deficiency can be included.

Contact Provita for further information.