Heat stress – The tell-tale signs

10th June 2022

It’s not always easy to pick up heat stress in dairy cows, but there are some subtle hints that could give the game away.

“Fertility is the first thing to be affected by warmer weather, and we only need temperatures to average more than 14°C in buildings to encounter drops in oestrus detection,” says Cargill ruminant manager Mark Scott.

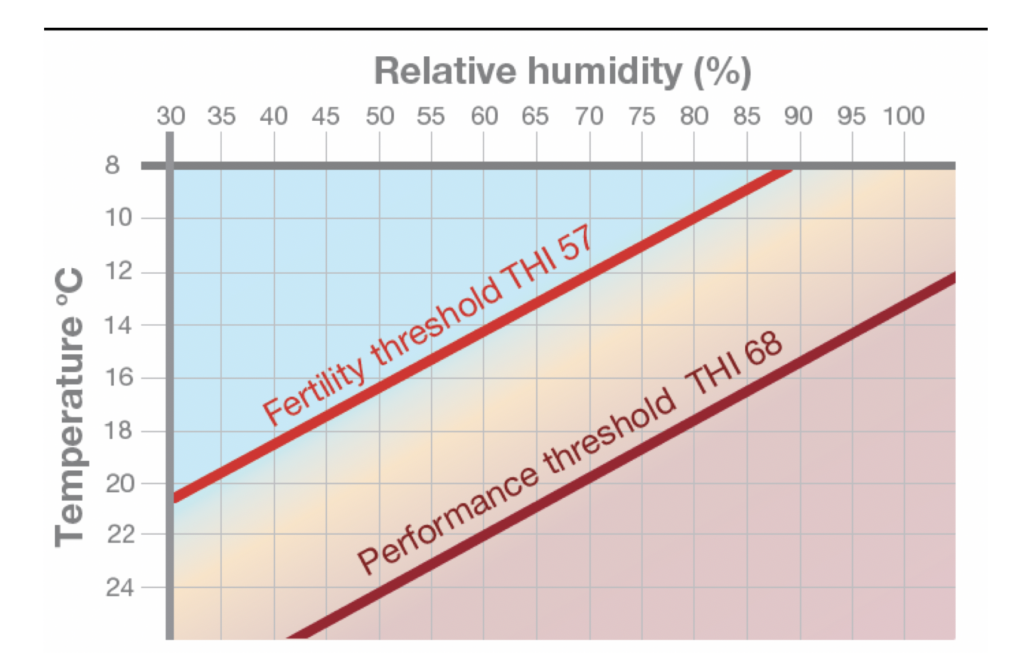

A combination of temperature and humidity, shown as a temperature and humidity index – or THI – provides an industry measure of heat stress risk, as shown in Figure 1. Certain thresholds are related to heat stress issues and the first to take its toll is fertility.

Under the UK’s typical relative humidity of 60%, oestrus can be affected when daily average temperatures are above 14⁰C, which is a THI of 57. “This happens at relatively low temperatures. We’re not talking about extremes, but modest spring temperatures and humidity levels.”

When daily average temperatures are above 20⁰C, conception rates can suffer. This is at a THI of 65.

Figure 1: Temperature and Humidity Index (THI) thresholds.

Milk yield and constituents are affected at higher temperatures, above 22⁰C, and typically when this is maintained as the at THI of 68, and typically only when this daily average temperature lasts for three or more days.

“But if we have a spike in temperatures to this sort of level, even for an hour or so, then cow behaviour can be affected. Cows spend more time standing in cooler areas and at water troughs, and respiration rates will increase. There will be fewer cows in cubicle and less time spent ruminating and eating.”

National THI network

Cargill UK runs an online THI monitoring service through summer with results from more than 30 THI data loggers installed on units across the UK. Live readings are relayed by WiFi to a dedicated web page with free access to all farmers. It shows the THI by region, alongside the actual temperature in sheds for the selected farms, and also provides the average temperature and THI for the past 24 hours and the week.

“Farmers can see when conditions are likely to create problems and additional actions can be taken to mitigate the effect of heat stress.

“We can provide farms with their own logger a seasonal summary of THIs that can be reviewed alongside milk records. This will highlight the effects on production and fertility of higher average temperatures, which will highlight the benefit of control measures and any necessary improvements that are needed.”

Figure 2: Average (blue line) and maximum (red line) THI readings from 30 sites across the UK (summer 2021).

Figure 2 shows the average and daily maximum THI readings recorded across Cargill’s network of loggers installed on UK dairy units in summer 2021. The THI in cow sheds is typically two or three points higher than outside conditions.

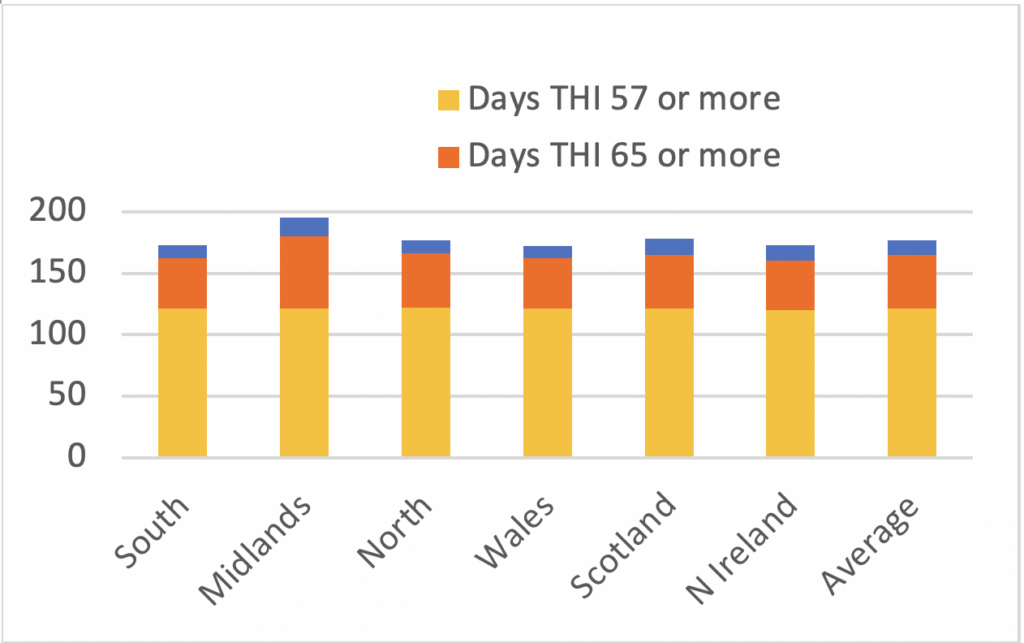

Cargill’s data logger results confirm that heat stress conditions are a national issue. “There’s no north/south divide – dairy herds in the north and Scotland are not exempt when it comes to heat stress in dairy cows.” This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: THI readings by region.

High heat cows

Mr Scott also reminds farmers that it’s not only outside temperatures that affect our cows, but that the high-performance cow will produce a lot of metabolic heat.

“Their rumens are like big furnaces,” he adds. “A cow giving 45kg of milk a day will produce 26% more metabolic heat than one giving 32kg a day. This heat needs to be dealt with.”

Prepare early

Cows must maintain a body temperature of between 38.5⁰C and 39⁰C. As temperatures rise, they can reduce their body heat by increasing blood flow to the skin, increasing breathing rate and reducing feed intakes, which means reduced rumen fermentation and less metabolic heat production.

“We need to be proactive in adapting management and feeding to prepare and help cows to cope with the heat. They feel the effects of warmer weather well before we do,” adds Mr Scott. “It is best not to wait until milk production drops – by then fertility will have taken a hit and this can have far-reaching consequences.”

More farmers are relying on fans. These should be well positioned and well maintained. Sprinklers, especially on fans in collecting areas at milking time, will also help to keep cows cool, and cows should have plenty of water and feed trough space and fresh clean water.

“And avoid grazing cows in paddocks with no shade when it’s warm – this might be obvious, but it’s surprising how often you see this happening.”

“Management can be tweaked too with earlier and later feeding times to make sure cows have fresh feed at cooler times of the day when they may be more inclined to eat.

CoolCow buffer

Fine-tuning rations pays dividends too. The specialised rumen buffer Equaliser CoolCow helps regulate core body temperature by hydrating the cow at the cellular level, and by restoring the electrolyte balance.

This powder additive, which is added to the lactating cow ration (TMR or compound feed) at a rate of between 100g and 150g/head/day from May to the end of September, has been shown to support yield, cow activity levels and pregnancy rates in farm trials.

In UK trials, fat-and-protein corrected milk yield was 0.5kg higher in the Equaliser CoolCow group throughout the trial period, and 1.5kg higher during the hottest weeks of the trial. And in the group of cows eligible to be bred during the trial, those in the Equaliser CoolCow group got in calf 17 days earlier than the control group.

Conservative estimates put the damages of heat stress – through lost milk, decreased fertility and less efficient use of feed – at between £40 and £85 a cow in a typical UK year.

“Keeping cows cooler will help to maintain rumen function, so intakes don’t falter,” he adds. “The aim is to keep cows comfortable and enable them to maintain their normal routines of lying and eating so that production and well-being is maintained throughout the summer.”

For more information click here