Trace minerals: What you need to know pre-calving

16th December 2020

Despite only being present in tiny amounts, trace minerals are absolutely vital to normal physiological functions and, consequently, the health and productivity of beef cattle. Even a subclinical deficiency can have a significant impact, writes vet and Virbac technical adviser, Kate Ingram.

Trace minerals play essential roles across a wide range of body systems. Manganese, for example, is required to produce important hormones such as oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone. Zinc is vital for healthy skin, hair and hooves, and plays a role in wound healing. The immune system requires zinc and selenium for antibody production. Copper also plays a role in an effective immune system, where it is required for white blood cell production, whilst also being important for good fertility.

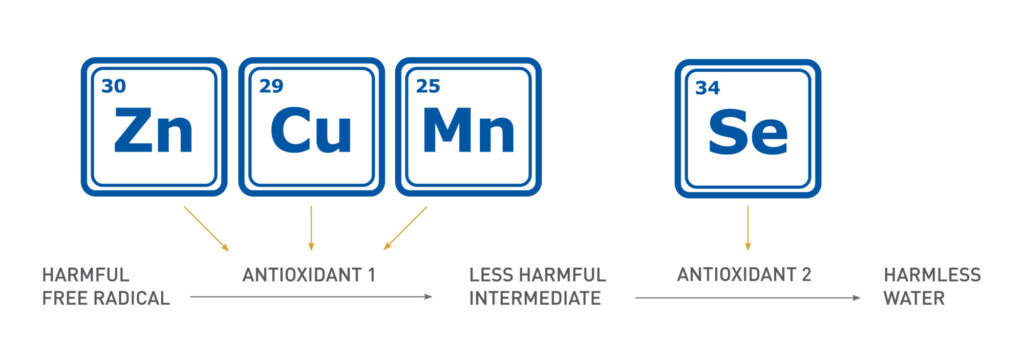

In addition, all four of these trace minerals are required by the body to form the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), essential in protecting against the effects of oxidative stress.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are constantly formed during normal metabolism. ROS cause ‘oxidative stress’ by damaging cells within the body, leading to disease and/or poor productivity. The body has a number of defence mechanisms to help limit the impact of these ROS, one of which being the aforementioned anti-oxidant enzymes, SOD and GPx. These enzymes act together to neutralise ROS to harmless water in a two-step pathway, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The role of trace minerals in reduction of free radicals through metallo-enzymes. Adapted from: Sordillo, L. and Aitken, S. (2009). Impact of oxidative stress on the health and immune function of dairy cattle. Veterinary Immunology & Immunopathology. 128:104–109.

The rate of ROS formation will increase in response to stress and increases in metabolic rate. Situations such as pregnancy or periods of rapid growth, and stressors such as weaning, mixing or transportation of youngstock are all high-risk periods in terms of oxidative stress and the associated cell damage.

Requirements for trace minerals fluctuate in cattle throughout the production cycle. Increased demand for these minerals may arise during periods of rapid growth or in response to vaccination, as the immune system mounts a response and produces antibodies.

An example of a high demand period in beef cattle would be the last trimester of pregnancy and then beyond, as the cow returns to cyclicity, ready to get back in calf. The cow must meet the demands of her growing calf (more than 75 per cent of foetal growth occurs during this period), whilst at the same time maintaining her own health and preparing for the demands of calving and milk production.

The trace mineral status of the neonatal calf depends on placental transfer of trace minerals and trace mineral concentrations in the colostrum, so maternal trace mineral status can have a significant effect on calf health. Cow’s milk is an exceptionally poor source of trace minerals. Fortunately, pre-birth loading of the liver occurs which provides a trace mineral store for the calf, in order to meet its trace mineral needs in the weeks after birth.

Once calved, the cow must feed her growing calf, restore uterine health and start cycling again. In beef herds aiming to hit the industry target of a 365-day calving interval, there is only a short window for the cows to recover from the demands of pregnancy and calving before mating begins, at which point they must be ready to conceive.

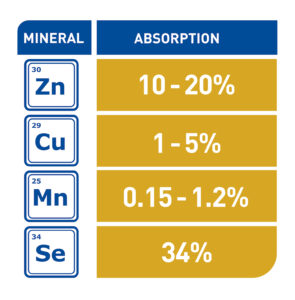

Figure 2: Bioavailability of oral trace minerals.

Source: Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, National Research Council, Seventh Revised Edition, 2001.

Many factors will affect the trace mineral levels in the cow. Not only does demand fluctuate, the amount of trace mineral the animals are taking in is also variable. Levels of trace minerals in feeds and pastures will vary, as will intakes of those feeds. Some trace minerals are very poorly absorbed when fed orally. Figure 2 illustrates the poor bioavailability of some of the trace minerals important for cattle health and shows that, for example, only a third of the selenium fed is likely to be absorbed, and less than 5 per cent of copper. In addition, the presence of ‘antagonist minerals’ such as iron, sulphur and molybdenum in the feed or water can also limit the uptake of trace minerals and result in lower-than-expected levels being absorbed into the cow.

This combination of fluctuations in demand for, and variable intake of, trace minerals can result in deficiencies developing, even in adequately supplemented animals. Ensuring adequate trace mineral levels during this period helps prevent subclinical deficiencies that may result from this imbalance of supply vs. demand and in the case of our beef cows, ensures immune function and fertility are not compromised at this key point in their production cycle.