Could better liver fluke control reduce methane emissions?

4th July 2022

As well as offering welfare and efficiency benefits, recent research has shown improving disease control could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 10%. Norbrook veterinary advisor Douglas Palmer offers advice on liver fluke testing and treatment, and the wider benefits of a good control programme.

AHDB estimates the cost of liver fluke to the UK agricultural industry to be around £300 million per year, and the impacts on growth rates and milk yield cost the UK cattle sector up to £40.4M annually. As the industry faces spiralling costs and increasing pressure to reduce GHG emissions, efficiency is more important than ever.

According to recent research1, gastrointestinal parasitism can also result in a minimum 10% increase in GHG emissions in lamb production, while liver fluke infection adds an extra 19 days to slaughter in cattle, reducing growth rate by 4% and adding 2% to the GHG footprint. In both scenarios, around half of the emissions will be methane.

Improving disease control doesn’t necessarily mean more medicines, but instead using them in a more targeted manner, Mr Palmer points out. Routinely monitoring worms and fluke is important for deciding if or when to treat, what product to use and whether the treatment has worked – as well as avoiding the expense and labour of unnecessary anthelmintic treatment.

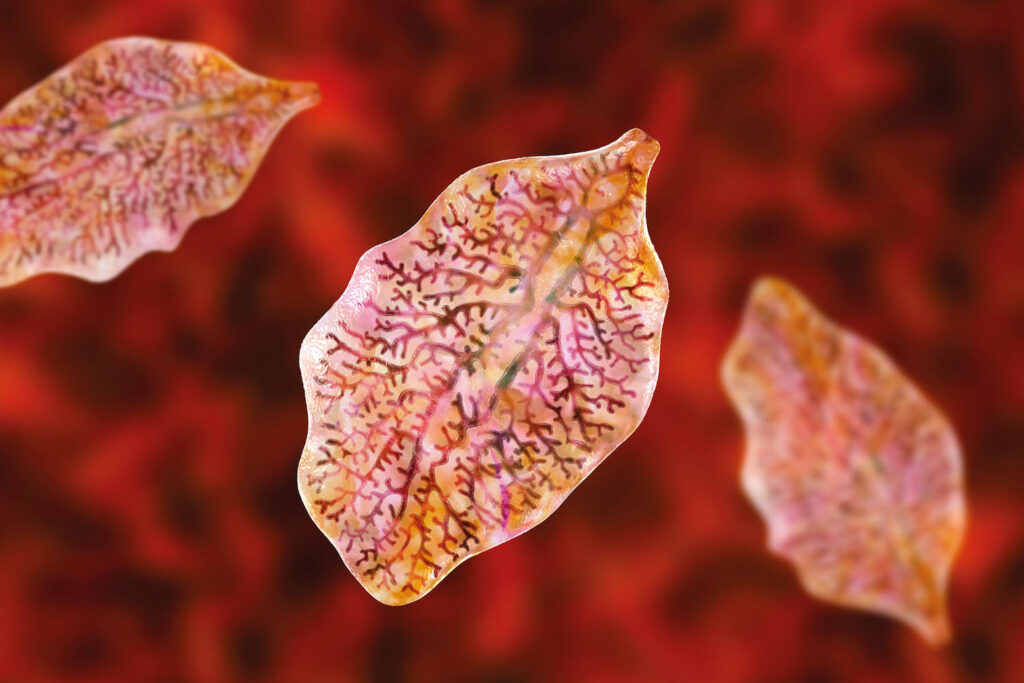

3D illustration of liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica).

When and where?

Generally liver fluke is present in the wetter parts of the country, and potentially areas with poorly draining soil which favours the intermediate host, the mud snail (Galba truncatula), Mr Palmer explains. In the UK, the climate and intermediate host mean the infective liver fluke metacercariae generally appear on pasture from late summer onwards.

Farms will likely have used a product to kill early immature fluke in that late summer/autumn period, but recent research has looked to better determine the correct treatment timings. “What they’ve found is that in some cases it can actually be later in the year before animals are picking up significant infection. Some farmers find they can actually sell lambs or house calves and cattle before they’ve had significant exposure to fluke. But the only way to know that is to test,” Mr Palmer comments.

Interestingly, he notes that there has been a steady decline in liver fluke diagnoses in veterinary labs across Great Britain since the last peak in 2012-13 – though the reasons for this are unclear – which emphasises the importance of testing before treatment. COWS and SCOPS offer a useful guide to test-based fluke control2.

Testing and treatment

Acute disease risk period: To detect fluke early, a monthly blood antibody test is recommended, which will give a positive result about two weeks after infection. To maximise effectiveness this test should be used for animals that have never been exposed to fluke – i.e. springborn lambs and calves. SCOPS/COWS recommend testing first season lambs and calves monthly in groups of 10 animals. Depending on where you are in the country, this will start around August/September.

Lambs and sheep are more at risk of acute liver fluke disease from early immature fluke. If you get a positive antibody test result in lambs, they should be treated with a triclabendazole drench, which is licensed to kill fluke from two weeks in

cattle and two days in sheep. However, Mr Palmer notes: “There is resistance reported in the UK so there’s a strong argument that suggests efficacy of triclabendazole should be preserved for the treatment of sheep with acute liver fluke disease. Cattle are generally less affected by acute liver fluke disease.”

He adds: “Because of that resistance it’s important to think about incorporating other actives into your system to try and reduce the selection pressure on that triclabendazole.”

COWS/SCOPS advises following up coproantigen and/or fluke egg counts testing later in the season for chronic infection.

Chronic disease risk period: This occurs in winter to spring/early summer depending on the farm and weather. For these later season infections, closantel will kill late immature and adult liver fluke, then after that albendazole, clorsulon or oxyclonazide are licensed to kill adult liver fluke.

Closantel is available for cattle and sheep. For sheep this is a drench, licensed to kill liver fluke from five weeks3 after they enter the animal, which would generally be used over wintertime. For cattle, closantel is available as a pour on either on its own or in combination with ivermectin; these will kill liver fluke from seven weeks after it enters the animal. There is currently no reported resistance in the UK.

For further information on liver fluke control programmes, speak to your vet or registered animal medicines advisor (RAMA).

References:

- Acting on methane: opportunities for the UK cattle and sheep sectors, Moredun Research Institute (on behalf of the Ruminant Health and Welfare Group), April 2022 https://ruminanthw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/SO-634-Ruminant-Report-Methane-April-2022-web.pdf (accessed 7th June 2022).

- www.sheepvetsoc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FINAL-Fluke-Diagnostics-Treatment.pdf

- Summary of Product Characteristics for Solantel Oral Suspension for sheep: https://www.vmd.defra.gov.uk/ProductInformationDatabase/files/SPC_Documents/SPC_1027058.PDF